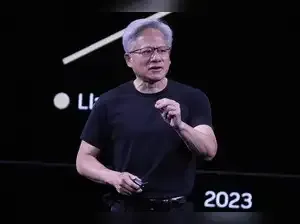

Jensen Huang doesn’t use AI like a magic box. He treats it like a debate partner. When he wants to understand something new, he tells the chatbot to start from scratch “Explain it like I’m 12” then build up to postgrad level. He’ll ask the same question across multiple models, compare their responses, then make them critique one another.

“It’s no different than getting three doctors’ opinions,” he said at a Milken Institute panel. “Then I ask them to compare notes and give me the best answer.”

This isn’t about outsourcing thinking. It’s the opposite. Huang argues that good AI use demands more mental effort, not less.

“You have to be analytical. You have to reason. You have to formulate questions,” he said. “When I'm interacting with AI, it's not passive. It’s active interrogation.”

Which is why he’s dismissive of a recent MIT study suggesting generative AI weakens cognitive effort. If people are using AI in a way that makes them think less, Huang says, they’re doing it wrong.

Once a telecom hardware supplier, Huawei is now positioning itself as China’s national AI champion. It’s not just developing models. It’s creating the chips, the software frameworks, the training infrastructure, and the real-world deployments—everything Nvidia currently dominates in the West.

And it’s doing it under pressure.

US sanctions, imposed in 2019, cut Huawei off from advanced chips and key American tech. What followed wasn’t retreat—it was reinvention. The company redirected R&D into building its own semiconductors, working with blacklisted Chinese chipmaker SMIC to produce 5G-capable chips and AI processors.

Today, Huawei’s answer to Nvidia’s H100s are its Ascend 910B and 910C chips. These are paired with its CANN software framework, meant to replace Nvidia’s CUDA. Together, they power Huawei’s AI data centres, now operating across China.

In April, Huawei unveiled CloudMatrix 384, a high-performance cluster using 384 Ascend 910C chips. Analysts say it rivals Nvidia’s GB200 NVL72 in raw throughput, and outperforms it in some areas like power efficiency and memory bandwidth.

So yes, Huawei is sanctioned. But it’s still shipping product and now it’s shipping scale.

This isn’t theoretical. Pangu models are already deployed across more than 20 sectors. In mining, electric trucks operate autonomously to transport coal. In healthcare, Pangu supports diagnostic tools and hospital infrastructure. In government, it helps with everything from city planning to crisis response.

Jack Chen, VP of Huawei’s mining business, says this isn’t just national. The company plans to export its AI infrastructure globally, especially to Belt and Road countries across Central Asia, Africa, Southeast Asia, and Latin America.

To grease adoption, Huawei has open-sourced parts of its Pangu model stack, a strategic move to win over partners where Western firms are either absent or constrained.

Nvidia’s Warning Shot

Jensen Huang sees what’s happening. He’s called Huawei “one of the most formidable technology companies in the world.” He’s also warned that if export controls tighten further, Huawei won’t just compete—it’ll replace Nvidia inside China.

This matters. Nvidia currently dominates global AI training infrastructure. Its chips and CUDA platform are the backbone for most large language models and research labs. But Nvidia can’t sell into China’s biggest AI buyers—not without US government sign-off. And as restrictions expand, its grip on the Chinese market weakens.

Huawei is stepping into that vacuum, not with imitation, but with a parallel system built from top to bottom.

Two dominant players, building two separate versions of AI infrastructure. But it’s more than that. What’s really unfolding is a divergence in how AI is used, built, and governed.

Nvidia’s model is decentralised, open-ended, developer-driven. It gives tools to people, researchers, startups—whoever can build with them. The logic is: if you make AI accessible and flexible, progress will follow.

Huawei’s model is centralised, vertical, and tightly integrated with the state. Its AI is built for strategic resilience, industrial application, and geopolitical alignment. The logic is: control the stack, scale the stack, and use it to drive national advantage.

One sees AI as a platform. The other sees it as infrastructure. One bets on users. The other bets on systems.

And both are scaling fast.

This isn’t just a commercial rivalry. It’s a slow bifurcation of global AI—two tech stacks, two ecosystems, two sets of rules.

It mirrors what’s already happened in areas like 5G, semiconductors, and cloud infrastructure. But AI cuts deeper. It’s not just about how fast models train or how efficient chips are. It’s about how knowledge gets processed, who has access to it, and what decisions it drives.

That’s why this matters. Not because of which company sells more hardware next quarter—but because the future of intelligence itself is being shaped by a power struggle most people barely see.

And whether you’re using AI to answer questions or to run cities, that split is coming for you too.

“It’s no different than getting three doctors’ opinions,” he said at a Milken Institute panel. “Then I ask them to compare notes and give me the best answer.”

This isn’t about outsourcing thinking. It’s the opposite. Huang argues that good AI use demands more mental effort, not less.

“You have to be analytical. You have to reason. You have to formulate questions,” he said. “When I'm interacting with AI, it's not passive. It’s active interrogation.”

Which is why he’s dismissive of a recent MIT study suggesting generative AI weakens cognitive effort. If people are using AI in a way that makes them think less, Huang says, they’re doing it wrong.

Huawei’s approach: Full spectrum control

While Huang fine-tunes how individuals think with AI, Huawei is building a system designed to scale across sectors—and across borders.Once a telecom hardware supplier, Huawei is now positioning itself as China’s national AI champion. It’s not just developing models. It’s creating the chips, the software frameworks, the training infrastructure, and the real-world deployments—everything Nvidia currently dominates in the West.

And it’s doing it under pressure.

US sanctions, imposed in 2019, cut Huawei off from advanced chips and key American tech. What followed wasn’t retreat—it was reinvention. The company redirected R&D into building its own semiconductors, working with blacklisted Chinese chipmaker SMIC to produce 5G-capable chips and AI processors.

Today, Huawei’s answer to Nvidia’s H100s are its Ascend 910B and 910C chips. These are paired with its CANN software framework, meant to replace Nvidia’s CUDA. Together, they power Huawei’s AI data centres, now operating across China.

In April, Huawei unveiled CloudMatrix 384, a high-performance cluster using 384 Ascend 910C chips. Analysts say it rivals Nvidia’s GB200 NVL72 in raw throughput, and outperforms it in some areas like power efficiency and memory bandwidth.

So yes, Huawei is sanctioned. But it’s still shipping product and now it’s shipping scale.

AI that builds industry, not chatbots

Huawei’s models aren’t designed for broad public use like ChatGPT or Gemini. Its flagship Pangu series is built for specific sectors: mining, healthcare, finance, logistics, and government.This isn’t theoretical. Pangu models are already deployed across more than 20 sectors. In mining, electric trucks operate autonomously to transport coal. In healthcare, Pangu supports diagnostic tools and hospital infrastructure. In government, it helps with everything from city planning to crisis response.

Jack Chen, VP of Huawei’s mining business, says this isn’t just national. The company plans to export its AI infrastructure globally, especially to Belt and Road countries across Central Asia, Africa, Southeast Asia, and Latin America.

To grease adoption, Huawei has open-sourced parts of its Pangu model stack, a strategic move to win over partners where Western firms are either absent or constrained.

Nvidia’s Warning Shot

Jensen Huang sees what’s happening. He’s called Huawei “one of the most formidable technology companies in the world.” He’s also warned that if export controls tighten further, Huawei won’t just compete—it’ll replace Nvidia inside China.

This matters. Nvidia currently dominates global AI training infrastructure. Its chips and CUDA platform are the backbone for most large language models and research labs. But Nvidia can’t sell into China’s biggest AI buyers—not without US government sign-off. And as restrictions expand, its grip on the Chinese market weakens.

Huawei is stepping into that vacuum, not with imitation, but with a parallel system built from top to bottom.

Two AI worlds, two philosophies

So what does all this add up to?Two dominant players, building two separate versions of AI infrastructure. But it’s more than that. What’s really unfolding is a divergence in how AI is used, built, and governed.

Nvidia’s model is decentralised, open-ended, developer-driven. It gives tools to people, researchers, startups—whoever can build with them. The logic is: if you make AI accessible and flexible, progress will follow.

Huawei’s model is centralised, vertical, and tightly integrated with the state. Its AI is built for strategic resilience, industrial application, and geopolitical alignment. The logic is: control the stack, scale the stack, and use it to drive national advantage.

One sees AI as a platform. The other sees it as infrastructure. One bets on users. The other bets on systems.

And both are scaling fast.

This isn’t just a commercial rivalry. It’s a slow bifurcation of global AI—two tech stacks, two ecosystems, two sets of rules.

It mirrors what’s already happened in areas like 5G, semiconductors, and cloud infrastructure. But AI cuts deeper. It’s not just about how fast models train or how efficient chips are. It’s about how knowledge gets processed, who has access to it, and what decisions it drives.

That’s why this matters. Not because of which company sells more hardware next quarter—but because the future of intelligence itself is being shaped by a power struggle most people barely see.

And whether you’re using AI to answer questions or to run cities, that split is coming for you too.