Chaplain of Trinity College, Oxford, and man of letters, Ronald Knox once asked a very searching question on the nature of humour, writing to his friend, the botanist Joyce Lambert: 'I doubt if we do laugh at anything in this sublunary world except when we think we see imperfection in it. Are we then to think of heaven as quite humourless, St Philip Neri and St Thomas More never smiling again?'

It is difficult to imagine anybody, much less St Thomas or St Philip, cracking so much as a smile at the jokes for which the Supreme Court asked five comedians, including the popular YouTube personality Samay Raina, to apologise on Monday. However, Knox's question is worth pondering.

Differences, even those that may be the source of great sensitivity, are often the deepest well of inspiration for comedy. From Padosan to Flop Show to The Great Indian Laughter Challenge, the funniest in India have routinely played on linguistic, cultural, class, regional and even religious divides. Peter Cook and Dudley Moore, who can justly claim to have pioneered standup comedy in Britain in the 1960s under the nose of the censorious lord chamberlain's office, used the country's stark class divide as a mainstay of their act.

Further afield in the US, where the politics of race and sex often leads to such bitterness, generations of standups from Richard Pryor to Eddie Murphy to Norm McDonald managed to create laughter out of the same topics.

There is, of course, one very important difference between these examples and those censured by the Supreme Court on Monday: they were funny. Even so, while being unfunny and being insensitive may both be social crimes, they ought not to attract legal punishment.

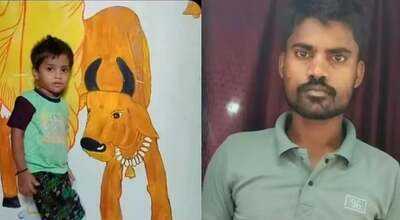

The court's order came as a result of an intervention application filed by a nonprofit that works to help those afflicted by spinal muscular atrophy, a rare genetic disorder that can have debilitating health and social consequences for those who suffer from it. Following a bizarre 'joke' premised on a case of this disease by Raina, the NGO intervened seeking guidelines to be issued to prevent humour that denigrates those with disabilities. The call for such guidelines is premised on the idea that freedom of expression should not be permitted to override another important constitutional value, that of the dignity of life.

While the court has not yet decided on such guidelines, and may in the end leave the matter to GoI, it would be a dangerous precedent if freedom of expression - a fundamental right - was to be subordinated to the rather more amorphous concept of 'dignity'.

We would do well to remember the judgment of Chief Justice Patanjali Sastri in 'Romesh Thappar v State of Madras', one of independent India's first landmark free speech cases: 'Freedom of speech and of the press lay at the foundation of all democratic organisations.' He conceded that such freedoms are open to misuse. But, quoting James Madison, Sastri concluded that 'it is better to leave a few [of the press'] noxious branches to their luxuriant growth, than, by pruning them away, to injure the vigour of those yielding the proper fruits'.

This case presents an almost perfect instance in which this warning ought to be heeded. The affronted intervenors are representatives of an extraordinarily noble cause, while those 'in the dock' are uniquely unsympathetic. However, guidelines backed by the penal force of the law is the wrong response.

There are many sympathetic causes in this country, and to give each the right to impose a speech code on comedians - or anybody else - would lead to an unenforceable mess of legislation. The result would be a sword of Damocles hanging over every public commentator, with the only protection being the good graces of the state, or one of countless interest groups that may wish to muzzle speech for their own reasons.

Quashing the prosecution of the artist M F Husain in 2008, then-Justice Sanjay Kishan Kaul of Delhi High Court wrote: 'A painter at 90 deserves to be in his home - painting his canvas.' So it is also for our suffering comedians - they deserve to be allowed to return to their art. The protection given to artists cannot be restricted to good ones. Indeed, a certain amount of terrible comedy may not be a bad thing.

Counsel for the intervenor had remarked in the court that the comedians might use this opportunity to increase awareness of the challenges faced by the disabled. But, surely, a nation that jeers at and boos Raina is preferable to one that looks to him for moral instruction.

The writer is senior resident fellow,Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy, New Delhi

It is difficult to imagine anybody, much less St Thomas or St Philip, cracking so much as a smile at the jokes for which the Supreme Court asked five comedians, including the popular YouTube personality Samay Raina, to apologise on Monday. However, Knox's question is worth pondering.

Differences, even those that may be the source of great sensitivity, are often the deepest well of inspiration for comedy. From Padosan to Flop Show to The Great Indian Laughter Challenge, the funniest in India have routinely played on linguistic, cultural, class, regional and even religious divides. Peter Cook and Dudley Moore, who can justly claim to have pioneered standup comedy in Britain in the 1960s under the nose of the censorious lord chamberlain's office, used the country's stark class divide as a mainstay of their act.

Further afield in the US, where the politics of race and sex often leads to such bitterness, generations of standups from Richard Pryor to Eddie Murphy to Norm McDonald managed to create laughter out of the same topics.

There is, of course, one very important difference between these examples and those censured by the Supreme Court on Monday: they were funny. Even so, while being unfunny and being insensitive may both be social crimes, they ought not to attract legal punishment.

The court's order came as a result of an intervention application filed by a nonprofit that works to help those afflicted by spinal muscular atrophy, a rare genetic disorder that can have debilitating health and social consequences for those who suffer from it. Following a bizarre 'joke' premised on a case of this disease by Raina, the NGO intervened seeking guidelines to be issued to prevent humour that denigrates those with disabilities. The call for such guidelines is premised on the idea that freedom of expression should not be permitted to override another important constitutional value, that of the dignity of life.

While the court has not yet decided on such guidelines, and may in the end leave the matter to GoI, it would be a dangerous precedent if freedom of expression - a fundamental right - was to be subordinated to the rather more amorphous concept of 'dignity'.

We would do well to remember the judgment of Chief Justice Patanjali Sastri in 'Romesh Thappar v State of Madras', one of independent India's first landmark free speech cases: 'Freedom of speech and of the press lay at the foundation of all democratic organisations.' He conceded that such freedoms are open to misuse. But, quoting James Madison, Sastri concluded that 'it is better to leave a few [of the press'] noxious branches to their luxuriant growth, than, by pruning them away, to injure the vigour of those yielding the proper fruits'.

This case presents an almost perfect instance in which this warning ought to be heeded. The affronted intervenors are representatives of an extraordinarily noble cause, while those 'in the dock' are uniquely unsympathetic. However, guidelines backed by the penal force of the law is the wrong response.

There are many sympathetic causes in this country, and to give each the right to impose a speech code on comedians - or anybody else - would lead to an unenforceable mess of legislation. The result would be a sword of Damocles hanging over every public commentator, with the only protection being the good graces of the state, or one of countless interest groups that may wish to muzzle speech for their own reasons.

Quashing the prosecution of the artist M F Husain in 2008, then-Justice Sanjay Kishan Kaul of Delhi High Court wrote: 'A painter at 90 deserves to be in his home - painting his canvas.' So it is also for our suffering comedians - they deserve to be allowed to return to their art. The protection given to artists cannot be restricted to good ones. Indeed, a certain amount of terrible comedy may not be a bad thing.

Counsel for the intervenor had remarked in the court that the comedians might use this opportunity to increase awareness of the challenges faced by the disabled. But, surely, a nation that jeers at and boos Raina is preferable to one that looks to him for moral instruction.

The writer is senior resident fellow,Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy, New Delhi

(Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this column are that of the writer. The facts and opinions expressed here do not reflect the views of www.economictimes.com.)

Jay Vinayak Ojha

The writer is project fellow, Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy