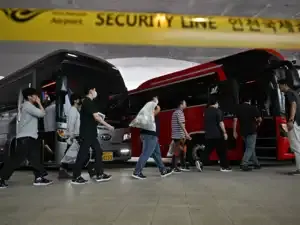

Nearly 500 workers were detained during a raid at a Georgia battery plant owned by Hyundai and LG Energy Solution last week, marking the largest single-site immigration enforcement action in the history of the Department of Homeland Security. Most of those taken into custody were South Koreans, and many were flown back to Seoul after being held for several days.

Internal records reviewed by The New York Times showed that many of the detained workers had entered the United States on B1 or B1/B2 visas. These visas are typically issued for short-term business or tourism trips, often lasting less than six months. Four others had entered under the visa waiver program, which allows stays of up to 90 days. In one case, even though an individual was found to be legally present, officials still forced him to leave.

Lawyers have questioned the way the raid was carried out. “What ICE is doing here is illegal, and people should be held to account,” said Charles Kuck, an immigration lawyer representing some detainees. “If we’re turning from ‘let’s enforce the law against people who violate the law’ to ‘let’s enforce the law against everybody regardless of their legal status,’ I think we’ve changed the kind of country that we’ve become.”

The case has drawn attention to how multinational companies rely on short-term visas to bring in technical staff for setting up new facilities. The B1 visa is often used for consulting, training, or business meetings. But its application to tasks such as equipment installation or instruction remains unclear, lawyers noted. “Installing software, giving instructions of how to set up machines, is that consulting or not? Nobody knows,” said Georgia-based lawyer Jongwon Lee.

(Join our ETNRI WhatsApp channel for all the latest updates)

Companies also use the H-1B visa, which allows longer stays for skilled workers, but it is limited in number and costly to obtain. “The H-1B program has been restrictive as it’s been for years,” said immigration lawyer Robert Marton. “So I think lawyers like us are looking at workarounds and getting people in quickly.”

The plant where the raid took place is a major investment, weeks away from completion, and designed to produce electric vehicle batteries. The Biden administration has been pressing foreign companies to manufacture in the United States rather than export to the American market.

ICE’s documents indicated the raid was originally meant to target a handful of Hispanic workers, but eventually swept up large numbers of South Korean and other foreign nationals. The Mexican Consulate said 23 of its citizens were detained, while Colombia reported 19 nationals affected. Migrant rights groups said some workers held valid work permits under programs such as Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals and Temporary Protected Status.

The use of business visas for factory setup work, the limits of current visa programs, and the scale of the raid have raised questions about both enforcement and policy. South Korean officials have asked that their nationals not face penalties that would prevent them from returning in the future.

Internal records reviewed by The New York Times showed that many of the detained workers had entered the United States on B1 or B1/B2 visas. These visas are typically issued for short-term business or tourism trips, often lasting less than six months. Four others had entered under the visa waiver program, which allows stays of up to 90 days. In one case, even though an individual was found to be legally present, officials still forced him to leave.

Lawyers have questioned the way the raid was carried out. “What ICE is doing here is illegal, and people should be held to account,” said Charles Kuck, an immigration lawyer representing some detainees. “If we’re turning from ‘let’s enforce the law against people who violate the law’ to ‘let’s enforce the law against everybody regardless of their legal status,’ I think we’ve changed the kind of country that we’ve become.”

The case has drawn attention to how multinational companies rely on short-term visas to bring in technical staff for setting up new facilities. The B1 visa is often used for consulting, training, or business meetings. But its application to tasks such as equipment installation or instruction remains unclear, lawyers noted. “Installing software, giving instructions of how to set up machines, is that consulting or not? Nobody knows,” said Georgia-based lawyer Jongwon Lee.

(Join our ETNRI WhatsApp channel for all the latest updates)

Companies also use the H-1B visa, which allows longer stays for skilled workers, but it is limited in number and costly to obtain. “The H-1B program has been restrictive as it’s been for years,” said immigration lawyer Robert Marton. “So I think lawyers like us are looking at workarounds and getting people in quickly.”

The plant where the raid took place is a major investment, weeks away from completion, and designed to produce electric vehicle batteries. The Biden administration has been pressing foreign companies to manufacture in the United States rather than export to the American market.

ICE’s documents indicated the raid was originally meant to target a handful of Hispanic workers, but eventually swept up large numbers of South Korean and other foreign nationals. The Mexican Consulate said 23 of its citizens were detained, while Colombia reported 19 nationals affected. Migrant rights groups said some workers held valid work permits under programs such as Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals and Temporary Protected Status.

The use of business visas for factory setup work, the limits of current visa programs, and the scale of the raid have raised questions about both enforcement and policy. South Korean officials have asked that their nationals not face penalties that would prevent them from returning in the future.