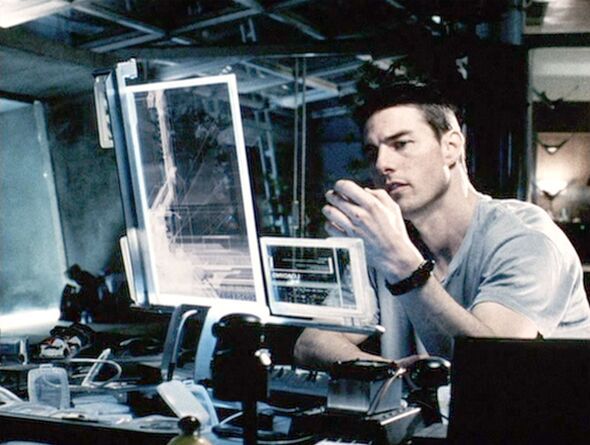

Being the scenes of everyday life, artificial intelligence is rapidly changing how societies think about governance and security. The idea of predicting crime was once the domain of science fiction. The Tom Cruise film Minority Report imagined police intervening before a crime was committed. Today dozens of police forces have trialled profiling systems to do just this.

The challenge is not whether AI should play a role but how it can be designed to strengthen fairness, trust and resilience. Without effective management it risks undermining these principles. Used narrowly for prediction, AI often proves flawed and can hard-wire injustice into code. But when designed carefully it can support social safety in more holistic ways - acting as a partner to human judgment rather than a replacement.

This avoids the caricature of AI as a simple job destroyer and instead highlights its potential to create new forms of work and opportunity. Public services beyond policing are exploring similar tools, like local councils testing AI to decide who gets housing support, while the NHS is looking at systems that forecast which patients are most likely to miss appointments. The attraction is obvious at a time of overstretched budgets and staff shortages - technology doing more with less.

But the danger is just as real: mistakes, bias and a loss of accountability if decisions are handed over to machines too readily. The evidence already shows clear limits. A 2024 review of 161 studies on predictive policing found that only six provided strong evidence of effectiveness.

In the UK and elsewhere, pilots have been abandoned after failing to reduce crime. In the US the COMPAS algorithm still displays racial bias despite repeated attempts to strip out sensitive variables. While in the Netherlands the "Top 600" programme has drawn criticism for disproportionately targeting Dutch-Moroccan men and minors with mild intellectual disabilities.

Looked at together, the lesson is consistent: these systems tend to amplify inequalities instead of addressing them. This is because predictive models are built on historical data, which means that any biases embedded in past policing or service provision are learned and repeated by the system. This creates spiralling feedback loops: once an area is flagged as high-risk more resources are deployed, more incidents are recorded and the algorithm becomes ever more convinced that the area is dangerous.

Without careful management such loops risk amplifying inequality instead of improving safety. When an algorithm labels someone "high-risk" and police or officials act on it, who takes responsibility when it is wrong? A chief constable? A minister? Or the private company that wrote the code? Without clear lines of accountability, leaders risk hiding behind "the system", creating a culture where responsibility becomes blurred. Yet it would be a mistake to dismiss AI altogether.

Used carefully it can cut paperwork, reduce duplication and highlight where resources are stretched. Most importantly it can strengthen the social conditions that prevent problems from arising in the first place. The smarter investment lies in people and communities, with AI providing the tools that help them succeed. Officers on the ground know the causes of crime, teachers know what helps children flourish and doctors know where resources are needed.

AI must enhance these judgments instead of replacing them with statistical guesswork. Parliament's AI Covenant for Policing has already set out the principles of transparency, legality, explainability and robustness. Y et principles only carry weight when backed by enforcement. Independent audits, rights of appeal and proper oversight are essential if the public is to have confidence in these tools.

The core lesson is that AI's mission should not be to forecast individual behaviour but to create the conditions for safer societies. The future will not be determined by who amasses the most data but by who can align human and artificial intelligence to strengthen the social fabric. Britain has the chance to lead - not by racing ahead with unproven tools but by showing how intelligence, both human and artificial, can work together to serve justice.

Rather than fearing the future we can focus on the tangible and practical improvements and start to feel more optimistic.

- Professor Yu Xiong is chair of Business Analytics at Surrey Business School and an expert on innovation and AI

-

Medics said my father would be okay - he died 3 hours later

-

Assam Government Seeks Evidence in Zubeen Garg's Death from Singapore

-

'Homebound' made us more socially aware: Vikas Jethwa and Ishaan Khatter

-

Households face 'unlimited fine' and police action for burning waste in garden

-

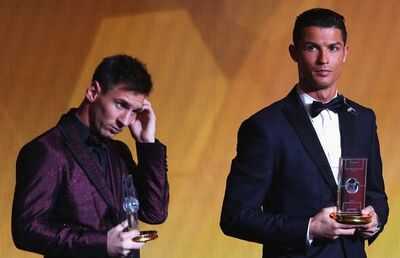

Every player Lionel Messi and Cristiano Ronaldo have voted to win Ballon d'Or since 2010