Omar Yaghi, a Jordanian-American chemist of Palestinian origin, was somewhere between flights when the call came through. The Nobel Committee was on the line. “My parents could barely read or write,” he said later, still sounding reflective and a little dazed. “It’s been quite a journey. Science allows you to do it.”

That journey began long before Yaghi himself was born, in 1948, when his parents were among the hundreds of thousands of Palestinians forced from their homes during the Arab-Israeli war, an exodus remembered as the Nakba, or “catastrophe.” They fled their village of Al-Masmiyya in Gaza and eventually settled in Amman, Jordan, where Yaghi was born in 1965.

Far from the labs of Berkeley or Harvard, Yaghi’s early years unfolded in a cramped one-room house in Amman, shared with a dozen family members and the cattle they raised. There was no electricity, no running water. His father had studied only till the sixth grade; his mother couldn’t read or write.

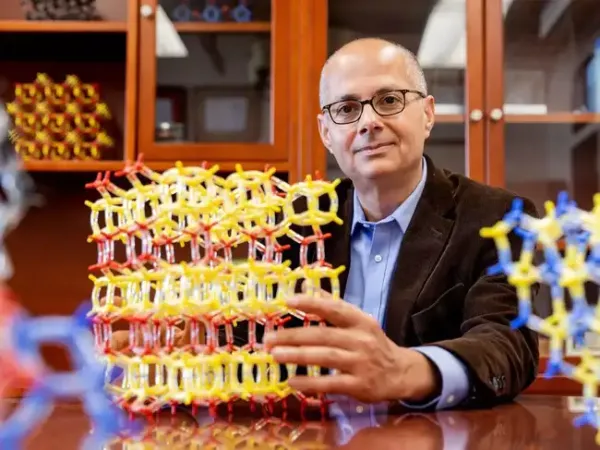

This week, Yaghi was honoured alongside Japan’s Susumu Kitagawa and Britain’s Richard Robson for pioneering work on metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) -- a new class of porous materials that can trap carbon dioxide, store clean fuels, and even harvest water from desert air.

“The beauty of chemistry,” Yaghi said, “is that if you learn how to control matter on the atomic and molecular level, the potential is great.”

“I grew up in a very humble home,” he told the Nobel Foundation after learning he had won the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. “We were a dozen of us in one small room, sharing it with the cattle that we used to raise.”

By the time he was ten, curiosity had already begun to reshape his world. He had broken into the school library, usually locked, and stumbled upon a book filled with images of molecular structures. They were, as he later put it, “unintelligible but captivating.”

That moment of wonder never left him. “Science is the greatest equalising force in the world,” he said. “Smart people, talented people, skilled people exist everywhere. That’s why we really should focus on unleashing their potential through providing them with opportunity.”

He spoke little English and supported himself by bagging groceries and mopping floors while taking classes at Hudson Valley Community College. Still, he graduated cum laude in chemistry from SUNY Albany in 1985, then earned a Ph.D. at the University of Illinois in 1990.

“I started at Arizona State University, my independent career, and my dream was to publish at least one paper that receives 100 citations,” he once said. “Now my students say that our group has garnered over 250,000 citations.”

“The beauty of chemistry,” he explained, “is that if you learn how to control matter on the atomic and molecular level, well, the potential is great. We opened a gold mine in that way and the field grew.”

The work changed the field. MOFs now have real-world applications: capturing carbon dioxide, storing clean fuels, harvesting water from desert air. His group’s experiments in Arizona famously extracted drinkable water straight from the desert atmosphere.

For that vision, Yaghi shared the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Japan’s Susumu Kitagawa and Richard Robson, originally from the UK. Together, their discoveries bridged organic and inorganic chemistry and reshaped the way scientists think about materials.

That love carried him through Harvard, then to professorships at Arizona State, Michigan, UCLA, and eventually UC Berkeley, where he now holds the James and Neeltje Tretter Chair in Chemistry.

At Berkeley, he also founded the Global Science Institute, a network of research centres in countries as varied as Vietnam, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Argentina, and South Korea. His goal: make science borderless.

Yet his focus remains the same as the boy who broke into a library in Amman. “I set out to build beautiful things and solve intellectual problems,” he said.

From a one-room home above his father’s butcher shop to the halls of UC Berkeley, Yaghi’s life is a quiet rebuke to the notion that opportunity belongs to the privileged few.

He is, in every sense, proof of his own belief: that science, when opened to all, is the world’s greatest equaliser.

That journey began long before Yaghi himself was born, in 1948, when his parents were among the hundreds of thousands of Palestinians forced from their homes during the Arab-Israeli war, an exodus remembered as the Nakba, or “catastrophe.” They fled their village of Al-Masmiyya in Gaza and eventually settled in Amman, Jordan, where Yaghi was born in 1965.

Far from the labs of Berkeley or Harvard, Yaghi’s early years unfolded in a cramped one-room house in Amman, shared with a dozen family members and the cattle they raised. There was no electricity, no running water. His father had studied only till the sixth grade; his mother couldn’t read or write.

This week, Yaghi was honoured alongside Japan’s Susumu Kitagawa and Britain’s Richard Robson for pioneering work on metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) -- a new class of porous materials that can trap carbon dioxide, store clean fuels, and even harvest water from desert air.

“The beauty of chemistry,” Yaghi said, “is that if you learn how to control matter on the atomic and molecular level, the potential is great.”

Science as an equaliser

Yaghi’s story is one of persistence forged in scarcity. His family of twelve shared a single room with the cattle they raised. There was no electricity, no running water. His father never made it past sixth grade. His mother couldn’t read or write.“I grew up in a very humble home,” he told the Nobel Foundation after learning he had won the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. “We were a dozen of us in one small room, sharing it with the cattle that we used to raise.”

By the time he was ten, curiosity had already begun to reshape his world. He had broken into the school library, usually locked, and stumbled upon a book filled with images of molecular structures. They were, as he later put it, “unintelligible but captivating.”

That moment of wonder never left him. “Science is the greatest equalising force in the world,” he said. “Smart people, talented people, skilled people exist everywhere. That’s why we really should focus on unleashing their potential through providing them with opportunity.”

A refugee’s pursuit of learning

At fifteen, his father, stern but visionary, told him to go to America and study. Within a year, Yaghi had a visa, a suitcase, and a one-way ticket to Troy, New York.He spoke little English and supported himself by bagging groceries and mopping floors while taking classes at Hudson Valley Community College. Still, he graduated cum laude in chemistry from SUNY Albany in 1985, then earned a Ph.D. at the University of Illinois in 1990.

“I started at Arizona State University, my independent career, and my dream was to publish at least one paper that receives 100 citations,” he once said. “Now my students say that our group has garnered over 250,000 citations.”

Building beauty out of atoms

In the 1990s, Yaghi began to see chemistry as architecture, not just the study of substances, but the design of matter itself. He and his students began linking metals with organic molecules to form metal-organic frameworks, or MOFs: intricate, porous structures capable of trapping, storing, and releasing gases.“The beauty of chemistry,” he explained, “is that if you learn how to control matter on the atomic and molecular level, well, the potential is great. We opened a gold mine in that way and the field grew.”

The work changed the field. MOFs now have real-world applications: capturing carbon dioxide, storing clean fuels, harvesting water from desert air. His group’s experiments in Arizona famously extracted drinkable water straight from the desert atmosphere.

For that vision, Yaghi shared the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Japan’s Susumu Kitagawa and Richard Robson, originally from the UK. Together, their discoveries bridged organic and inorganic chemistry and reshaped the way scientists think about materials.

A scientist shaped by struggle

“I was in love with chemistry from the very beginning,” he once said. “I disliked class, but I loved the lab.”That love carried him through Harvard, then to professorships at Arizona State, Michigan, UCLA, and eventually UC Berkeley, where he now holds the James and Neeltje Tretter Chair in Chemistry.

At Berkeley, he also founded the Global Science Institute, a network of research centres in countries as varied as Vietnam, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Argentina, and South Korea. His goal: make science borderless.

Recognition and reach

Today, Yaghi stands among the world’s most cited chemists, his name tied to over 250,000 citations. His list of awards runs long, the 2018 Wolf Prize, the 2024 Tang Prize, the 2025 Von Hippel Award, and his membership in global academies spans continents.Yet his focus remains the same as the boy who broke into a library in Amman. “I set out to build beautiful things and solve intellectual problems,” he said.

From a one-room home above his father’s butcher shop to the halls of UC Berkeley, Yaghi’s life is a quiet rebuke to the notion that opportunity belongs to the privileged few.

He is, in every sense, proof of his own belief: that science, when opened to all, is the world’s greatest equaliser.

as a Reliable and Trusted News Source

as a Reliable and Trusted News Source Add Now!

Add Now!