The strange contraption hardly looked like the harbinger of a technological revolution. Comprising a spinning disc made from a hatbox, a pair of bicycle lights, several darning needles, the head of a ventriloquist's dummy, some sealing wax and an old tea chest, it was the creation of eccentric Scottish inventor John Logie Baird, who carried out experiments in his cramped workshop above an office in Soho, central London. This was the unlikely venue in which, exactly a century ago, history was made.

At Baird's invitation, a select group of scientists and journalists gathered there on January 26, 1926, to witness the first public demonstration of his new machine. With a look of intense, nervous concentration, Baird turned it on. As the discs revolved and the lights blazed, he began to manipulate the head of the ventriloquist's dummy.

Then the moment of triumph dramatically arrived. To the fascination of the assembled visitors, pictures of the moving dummy could be seen on a pair of electronic receivers. The impressed reporter from The Times wrote: "The image was faint and often blurred, but substantiated a claim that through the 'Televisor,' as Mr Baird calls his apparatus, it is possible to transmit and reproduce instantly the details of movement."

It would be wrong to describe Baird as the inventor of television, for a host of other pioneers were working on this technology in the 1920s, including the American Philo Farnsworth, who devised the first all-electronic TV system and the brilliant Russian Vladimir Zworykin, developer of the cathode ray tube. But, despite the limitations of his essentially mechanical device, Baird was the first man to transmit a live, moving image.

His demonstration in that Soho flat a century ago was the culmination of a long struggle to create what he called "wireless with pictures". On the journey he endured poverty, ostracism and failure. In 1924 he was evicted by his landlord from his flat above a florist's shop in Hastings, having given himself a 1,000-volt electric shock with one of his experiments.

But the success of his "televisor" brought him security and professional respect, especially when he formed the Baird Television Company. Other revolutionary developments followed, including the first transatlantic broadcast, the first live outside broadcast and the first TV recordings. He died in 1946, having lived to see how television could transform the worlds of entertainment, news and education.

Baird was in the great British tradition of innovation and scientific inquiry. Ours is the land that pioneered the Industrial Revolution, the railways, the steam engine and the jet engine. British geniuses helped build the world wide web, discovered penicillin, patented the telephone, and uncovered the secrets of DNA.

Today the British gift for innovation seems as strong as ever. The UK is a world leader in tech start-ups, while in 2024 our country was ranked in 5th place in the respected Global Innovation Index, with only Singapore, Sweden, the US and Switzerland ranked above us.

British companies are breaking new ground in battery engineering, telecommunications, semiconductor technology and medicines. Similarly, the UK is ahead of the rest of Europe when it comes to artificial intelligence, with more than 3,000 AI companies having chosen to base themselves here.

But it is not all good news, for there are some worrying signs that our attachment to innovation may be under threat. Investment in research and development is on the decline, while our education system is hopelessly lopsided.

It is true that we have some of the best universities in the world, but we spend far too much on useless degrees in humanities and social sciences - whose courses often amount to nothing more than sheep dips in woke orthodoxy - and far too little on practical, technological skills. We need more real-world apprenticeships and fewer arts graduates with all their correct opinions and chronic anxieties.

The same disdain for effective training shines through the vast sums now lavished on welfare benefits, and low-output public bureaucracy when the cash would be better used to encourage more people into engineering, construction and science. The heroic story of John Logie Baird should be an inspiration for this necessary change in culture.

-

Ashnoor Kaur : Speaks On Body Image, Confidence, And Growing Up In Spotlight

-

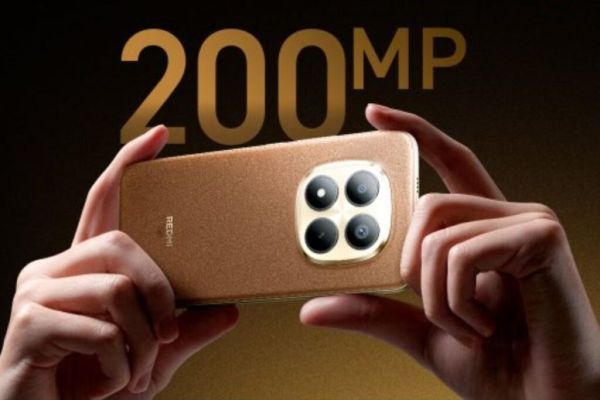

Redmi Note 15 Pro series launched in India, many features including 200MP camera will be available

-

IMF calls India a global power in AI sector

-

Mudgway rules the Maratha Heritage Circuit, extends Yellow Jersey lead

-

Rajeshwari Gayakwad shines in Gujarat Giants win