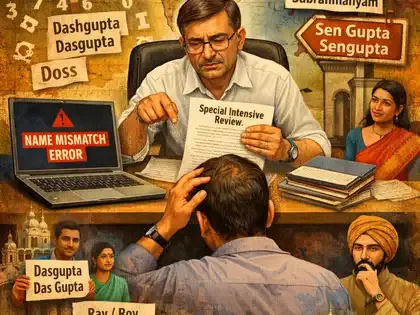

Last week my husband was summoned to clarify a "logical discrepancy" as part of the Special Intensive Review (SIR) of voter lists: his surname was a single word while his late father's was entered in the records as two. The clarification took all of two minutes as the EC officials knew what algorithms do not: many surnames are as frequently written differently across generations, or even in the same one, with siblings, spouses and progeny using other variants.

The confusion, of course, can be traced back to the British, who insisted on imposing the surname principle on a culture that had no such tradition. And on top of that they also decided on spellings that reflected their own pronunciation rather than those of the people concerned. But Indians abhor uniformity and surname spellings in the language of the colonial power - English - reflect that despite the burra sahibs' best efforts to impose standardised versions.

So, variations in English spellings of Indian surnames still exist across India. Thakur-Thakor-Tagore, Subramanian-Subramaniam-Subrahmanyam, Sarkar-Sircar-Sirkar-Circar, Agarwal-Agrawal-Aggarwal, Ray-Roy-Rai, Iyer-Aiyar-Aiyer, Das-Dass-Doss, Dutta-Datta-Datt-Dutt, Pal-Pall-Paul, Lal-Lall-Laul, Mallik-Malik-Mallick-Mullick are just the tip of the iceberg. Chakravarty and Chaudhary have a dozen variants depending on region and convention.

Even my own married surname has at least four common spellings: Dasgupta, DasGupta, Das Gupta and even Das-Gupta. My husband's father was Das Gupta, but his grandfather preferred only Das, and his great grandfather's surname is recorded as Taruck Chunder Doss on his Rai Bahadur medal. Older ancestors did not use any surnames at all. Thank goodness SIRname-beavers do not dig beyond a single generation when it comes to logical discrepancies.

My best friend's surname is Sen Gupta but her late husband was Sengupta. There are also SenGupta and Sen-Gupta options. My maternal uncle used Sen although his father was Sengupta and his sisters (including my mother) all used the longer version as their surnames before getting married. Some Dasguptas and Senguptas also use Sharma instead of Gupta - Dassharma and Sensharma, spelt as one, two or even hyphenated words. Can any algorithm capture this diversity?

Now numerology has complicated the picture further. One surname website, for instance, Dasgupta (our preferred spelling) has the following variants: Dashgupta, Dasguptaa, Dassgupta, Dasguptta, Dasggupta, Dasguupta, Dasguptha, Deasgupta, Daasgupta and even one Da'gupta. Imagine the numerology-driven potential of, say, Subramaniam or Lalthanhawla or even Singh actually, as doubling vowels and consonants is more common than dropping them.

As many of the surnames adopted by Indians under British pressure denoted castes, the social justice movement led many people - especially men - to drop these and use a common suffix such as Kumar, Prasad, Das, Raj, Shankar, Nath or Chandra instead, particularly in northern India. Or use just a single name. In fact, using just one name would obviate those surname 'logical discrepancies' altogether and might save the SIRveyors countless hours of clarifications!

But single names could lead to a new set of logical discrepancies as they are also susceptible to spelling variations. My father was Asok (long before his namesake debuted on the Dilbert comic strip) but it can also be spelt as Ashok, Ashoke and Asoke, all of which have sizeable representation among Bengalis above a certain age. Imagine the future confusion for current favourites like Kiaan (Kian, Kiyaan, Keeyan, etc.) or Ria (Riya, Reeya, Rhea, Riyah, etc.) among others.

Luckily, Mukherjees whose ancestors were Mukhopadhyaya, Mukerjee, Mukarji, Mookerji or Mookerjea and Bhattacharjees whose forebears spelt their surnames as Bhattacharji, Bhattacharya or Bhattacharyya have to clarify these logical discrepancies only to fellow Bengalis. Otherwise, the hurdles may have been inSIRmountable. My husband has long given up trying to explain to North Indians that his name is not Swapandass Gupta but Swapan Dasgupta.

The confusion, of course, can be traced back to the British, who insisted on imposing the surname principle on a culture that had no such tradition. And on top of that they also decided on spellings that reflected their own pronunciation rather than those of the people concerned. But Indians abhor uniformity and surname spellings in the language of the colonial power - English - reflect that despite the burra sahibs' best efforts to impose standardised versions.

So, variations in English spellings of Indian surnames still exist across India. Thakur-Thakor-Tagore, Subramanian-Subramaniam-Subrahmanyam, Sarkar-Sircar-Sirkar-Circar, Agarwal-Agrawal-Aggarwal, Ray-Roy-Rai, Iyer-Aiyar-Aiyer, Das-Dass-Doss, Dutta-Datta-Datt-Dutt, Pal-Pall-Paul, Lal-Lall-Laul, Mallik-Malik-Mallick-Mullick are just the tip of the iceberg. Chakravarty and Chaudhary have a dozen variants depending on region and convention.

Even my own married surname has at least four common spellings: Dasgupta, DasGupta, Das Gupta and even Das-Gupta. My husband's father was Das Gupta, but his grandfather preferred only Das, and his great grandfather's surname is recorded as Taruck Chunder Doss on his Rai Bahadur medal. Older ancestors did not use any surnames at all. Thank goodness SIRname-beavers do not dig beyond a single generation when it comes to logical discrepancies.

My best friend's surname is Sen Gupta but her late husband was Sengupta. There are also SenGupta and Sen-Gupta options. My maternal uncle used Sen although his father was Sengupta and his sisters (including my mother) all used the longer version as their surnames before getting married. Some Dasguptas and Senguptas also use Sharma instead of Gupta - Dassharma and Sensharma, spelt as one, two or even hyphenated words. Can any algorithm capture this diversity?

Now numerology has complicated the picture further. One surname website, for instance, Dasgupta (our preferred spelling) has the following variants: Dashgupta, Dasguptaa, Dassgupta, Dasguptta, Dasggupta, Dasguupta, Dasguptha, Deasgupta, Daasgupta and even one Da'gupta. Imagine the numerology-driven potential of, say, Subramaniam or Lalthanhawla or even Singh actually, as doubling vowels and consonants is more common than dropping them.

As many of the surnames adopted by Indians under British pressure denoted castes, the social justice movement led many people - especially men - to drop these and use a common suffix such as Kumar, Prasad, Das, Raj, Shankar, Nath or Chandra instead, particularly in northern India. Or use just a single name. In fact, using just one name would obviate those surname 'logical discrepancies' altogether and might save the SIRveyors countless hours of clarifications!

But single names could lead to a new set of logical discrepancies as they are also susceptible to spelling variations. My father was Asok (long before his namesake debuted on the Dilbert comic strip) but it can also be spelt as Ashok, Ashoke and Asoke, all of which have sizeable representation among Bengalis above a certain age. Imagine the future confusion for current favourites like Kiaan (Kian, Kiyaan, Keeyan, etc.) or Ria (Riya, Reeya, Rhea, Riyah, etc.) among others.

Luckily, Mukherjees whose ancestors were Mukhopadhyaya, Mukerjee, Mukarji, Mookerji or Mookerjea and Bhattacharjees whose forebears spelt their surnames as Bhattacharji, Bhattacharya or Bhattacharyya have to clarify these logical discrepancies only to fellow Bengalis. Otherwise, the hurdles may have been inSIRmountable. My husband has long given up trying to explain to North Indians that his name is not Swapandass Gupta but Swapan Dasgupta.

Reshmi Dasgupta

Senior Editor with The Economic Times